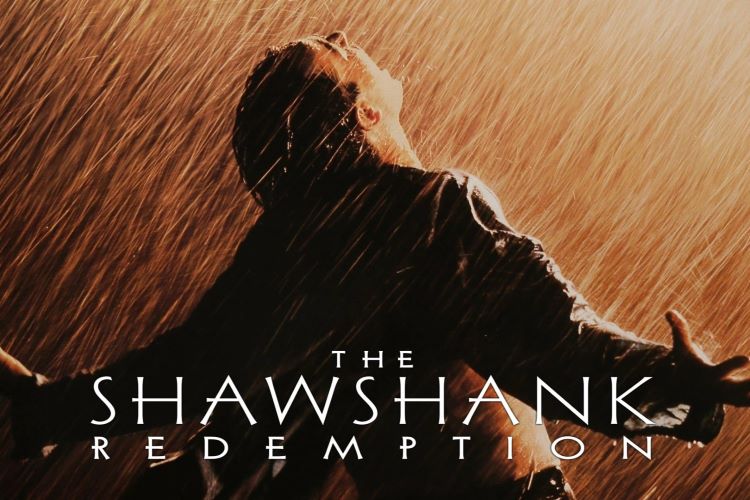

Get busy living, or get busy dying

Main Cast: Tim Robbins, Morgan Freeman

Director: Frank Darabont

When I was twelve years old, I read my first book by Stephen King. Being more or less nocturnal, I found myself deep into The Shining in the middle of the night. At the time we had a new kitten that delighted in jumping onto my bed under the covers, scaring the crap out of me. Looking back, I’m lucky I didn’t have a cat/Stephen King induced heart attack in the middle of one of those nights. That book scared the hell out of me and I was hooked for good. I’ve read nearly everything the man has written, and seen a good number of the movies based on his frantic scribblings. More often than not I want to kick myself for bothering to see the movies. I’m always disappointed. The characters aren’t as true or engaging; the supernatural is hokey and poorly presented, the writing stiff and clunky. It makes me sad to see books I like turned into films I hate. All those cranky King movie feelings changed in the first fifteen minutes of the remarkable adaptation of the novella Rita Hayworth and the Shawshank Redemption. No other King work has been turned into such an astoundingly worthy, fully engaging and beautifully realized portrait of the written word.

I believe in two things: discipline and the Bible. Here you’ll receive both. Put your trust in the Lord; your ass belongs to me. Welcome to Shawshank. – Warden Morton

Frank Darabont’s film, with the shortened title The Shawshank Redemption opens with a very drunk Andy Dufresne (Tim Robbins) brooding in his car outside a house. We later learn that this is the house in which Andy’s wife and her lover were found shot to death. We also learn that not only did Andy “dispose” of the gun we see him holding, but he has no other alibi except his word that he did not go into that house and kill those two people. Andy is as good as convicted before he ever stands trial. The film is the tale of Andy’s time at Shawshank prison, where he is sentenced to spend two consecutive life terms.

He arrives at Shawshank in 1947, quiet, stooped, without any presence or bluster. He keeps to himself, seemingly above all the prison yard politicking – earning himself a bit of a reputation as a snob. The educated banker who thinks he’s better than everybody else. When he finally does reach out, it’s to Red (Morgan Freeman) and only because Red “gets things”, and Andy wants a small rock hammer to carve things like chess pieces in his cell. Thus begins a friendship that will carry the narrative force of the movie. Red tells us the story of Andy; we see his prison tenure through Red’s eyes and Red’s words. We are not an omniscient viewer. We know what Red knows. As he describes events, we see them, but we are not inside Andy’s head. We’re in Red’s. This is the device that allows Darabont to keep Andy at arm’s length from the viewer. He always remains a little bit of a mystery, even as we learn more and more about the things he manages to accomplish during his years at Shawshank. Mystery is one of the things that makes Andy interesting. We aren’t focused on his every expression, nor are we privy to his every move. His motives are his own, keeping us surprised by his actions.

The other result of Red being our primary storyteller is that we get more than just one story. We get bits and pieces of many stories as they intersect with that of either Red or Andy. We become familiar with the inmates that make up the core group of friends that the two men share throughout the years. We fear and loathe the guards and warden right along with them. Never making excuses or presuming he doesn’t belong there, Red manages to capture the enormous psychological toll that prison takes on any man, guilty or innocent. We get all of these things, but not at the expense of the story, or in addition to the story, rather they become part of the story. All of the little messages and various bits of nuance are woven right into the core narrative. We never waiver from our focus on Andy, yet somehow manage to become attached to all sorts of peripheral characters as well.

As Andy spends more and more of his life in Shawshank, we learn what it takes for him to survive there. Not just fighting off those who would do him harm, but fighting the psychological obstacles that make men crack in a place where hope is dim and not encouraged. The boredom, the abuse, the rigidity, the loss of more than freedom. The loss of self that is right around every corner in a place that never changes. And perhaps most devastating, living with the regrets or injustices or anger that knock around in a person’s head when the lights go out. Andy is an encapsulation of all the things that prison takes from a person, and the small things that can make the difference between hope and resignation. The film is not about bashing the criminal justice system, not at all. It’s about one man and how he lives within that system. It’s about the institutionalization of the lifers, the survival of the fittest that gets skewed into the survival of the one with the least to lose, the desperate attempt not to be that person that has nothing left to lose. Andy isn’t fighting “The Man”, he’s fighting himself, fighting to keep his identity in a world designed to rob him of exactly that. We cheer for him because he won’t give himself over to the system, he won’t forget that there is something outside the walls of Shawshank. Even though to hold onto those things may do nothing more than torment him as the years pass, he refuses to give that last part of himself away. For that we admire him, not caring much about his guilt or innocence, just wanting to see him survive to hope another day.

Frank Darabont makes this movie sing. As both writer and director, he succeeds. Having great source material is one thing; successfully adapting it for the screen is something entirely different. While The Shawshank Redemption is fairly faithful to the novella, and certainly faithful in feel, tone and spirit, it is Darabont who brings these characters off the page and onto the screen. He gives us dialogue that is almost cryptic at times, yet is never without clear intent. His scenes carry emotional weight without long speeches, rather with tone and pace and the strength of the few words necessary. His prison is neither overly harsh nor overly cozy. It feels real. The slamming of cell doors, the ugly, barren exercise yard, the dull eyes and slow shuffle of idle men on perpetual hold. The times where a little life is breathed into the place stand out – as well they should. Music, a movie, a beer, all seem brighter than life, more real than real. They don’t belong here, so their presence is keenly felt.

And keenly visualized. Cinematographer Roger Deakins plays out the film on a palette of muted colors and drab, ugly cell-blocks. Every shot screams prison. The spaces feel crowded and dank, the buildings seem to crumble as we look at them, the men all look the same. Same clothes, same shoes, same dead, dull eyes. There are no camera acrobatics here to add visual interest to a scene – it isn’t needed. This place is all about sameness, and that’s what Deakins delivers so perfectly. The times where something needs to stand out it’s like a rose bush in a desert. Ordinary thing, but extraordinary in this place. The visuals are complimented by a score (Thomas Newman) highlighted by a soft, minor key piano that is as muted as the colors. We get some soaring instrumentals later, but they, too, are entirely appropriate.

Darabont would not have succeeded had it not been for the pitch perfect performances of both Freeman and Robbins. As well as virtually every other member of the cast. Morgan Freeman makes Red into a sort of prison conduit. Not only of goods but of history as well. He is a watcher, an observer of behavior in this strange place. It is Red who sees the larger truths of prison life. Freeman plays him as both a powerful man within the prison community and a scared man who has learned when to shut his mouth and close his eyes. Straddling this line is not an easy task, and Freeman does a fantastic job of making Red intuitive, realistic and keenly aware without ever forgetting that he is at the mercy of exactly the same forces as everyone else. A superb performance.

Tim Robbins is Andy Dufresne. I can’t remember how I pictured Andy when I read the book, because Robbins effectively erased that image and supplanted it with his own stooped shoulders and slow smile. He’s a big man who knows how to make that height feel like a burden, something to be borne rather than celebrated. Andy never seems larger then the other inmates in physical stature. He only becomes special through action and word, and then only gradually. Robbins’ line delivery is deliberate without being slow, his emotions are almost always guarded with only the occasional peek of what he really feels. Those scenes in which Andy lets some of that emotion pour out, even for a brief moment, are the most powerful in the film. While I don’t begrudge Freeman his Oscar nomination for this film for a second, this is Robbins’ show. The movie is his to make or break, and he makes it with one of the best performances of his career.

The peripheral players are equally wonderful. Clancy Brown as the sadistic guard Hadley is tremendous. His emotionless brutality combined with his ignorant blowhard persona make for one truly scary man with a club. Brown makes him five parts menace to one (very small) part stand up guy. Each time you think he might be turning into a human being, he proves you wrong. The actors playing the other inmates, particularly James Whitmore and William Sadler, manage to give their characters personality and charm without a whole lot of screen time. And last but most certainly not least is Bob Gunton as Warden Morton. So smug. So smarmy. So corrupt. All under the veil of a faux-Christianity so thick it’s suffocating. Gunton is perfectly loathsome. Perfectly.

It’s hard to write about a movie you love. You want others to love it too, so you try and highlight all the individual components that make the movie great. But that isn’t really why you love the movie. It isn’t because the writing is great, or the performances wonderful, or the source material delightful. All of those things need to be there, of course, but there’s just more to it than that. There’s that palpable “click” of everything working together, everyone being on the same page, every detail somehow swirling into the greater whole as if by magic. I’ve always wondered if those making a film know when the magic is there during the process. I can only imagine that they do, that they feel it too, making the production sweeter, the outcome richer. The Shawshank Redemption, a story of harsh reality, unreasonable hope and the life of one ordinary, extraordinary man, manages to capture lightening in a bottle. The magic is there, and fortunate are those of us that get to share it.

Hope is a good thing, maybe the best of things, and no good thing ever dies. – Andy Dufresne

Sue reads a lot, writes a lot, edits a lot, and loves a good craft. She was deemed “too picky” to proofread her children’s school papers and wears this as a badge of honor. She is also proud of her aggressively average knitting skills She is the Editorial Director at Silver Beacon Marketing and an aspiring Crazy Cat Lady.

Comments

Marc X

I enjoyed your review. Though not just because I agree with it. Your words are just so...earnest.

Sue Millinocket

to Marc X

Hi Marc, Thanks - it is an earnest review isn't it? Lol, I love the movie and must have been going through a "serious critic" phase when I wrote this.